Major Protestant beliefs

When talking about the Protestant Beliefs we should know that The chief characteristics of original Protestantism were the acceptance of the Bible as the only source of infallible revealed truth, the belief in the universal priesthood of all believers, and the doctrine that a Christian is justified in his relationship to God by faith alone, not by good works or dispensations of the church. There was a tendency to minimize liturgy and to stress preaching by the ministry and the reading of the Bible. Although Protestants rejected asceticism, an elevated standard of personal morality was advanced; in some sects, notably Puritanism, a high degree of austerity was reached. Their ecclesiastical polity, principally in such forms as episcopacy (government by bishops), Congregationalism, or Presbyterianism, was looked upon by Protestants as a return to the early Christianity described in the New Testament.

Protestantism saw many theological developments, particularly after the 18th cent. Under the influence of romanticism, which stressed the subjective element in religion rather than the revelation of the Bible, the formal systems of early Protestant theology began to dissolve; this doctrine was best expressed by Friedrich Schleiermacher, who placed religious feeling at the center of the Christian life. Along with this came the assertion that the fatherhood of God and the unity of humanity were the basic themes of Christianity. Later there was a neo-orthodox movement, which, under the leadership of Karl Barth and Reinhold Niebuhr, sought a return to a theology of revelation; a new school of Bible interpretation as expressed in the work of Rudolf Bultmann; and a theology, derived in part from existentialism, developed by Paul Tillich.

Main principles of protestant beliefs:

Various experts on the subject tried to determine what makes a Christian denomination a part of Protestant Beliefs. A common consensus approved by most of them is that if a Christian denomination is to be considered Protestant, it must acknowledge the following three fundamental principles of Protestantism.

Scripture alone:

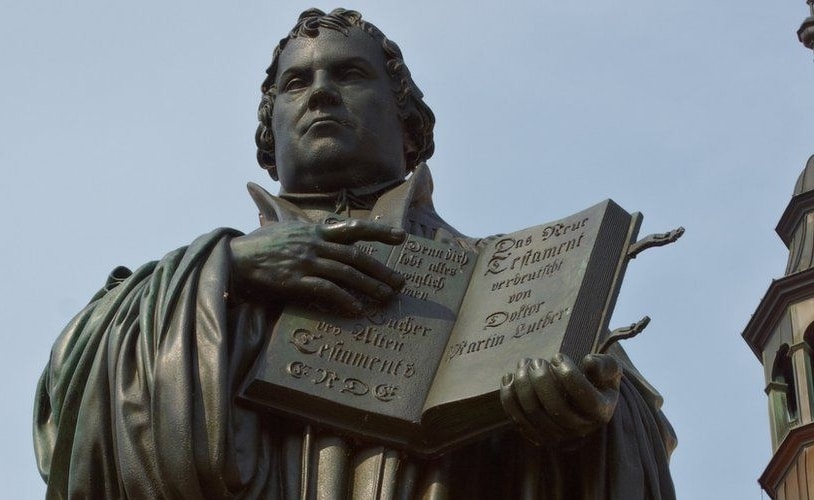

The belief, emphasized by Luther, in the Bible as the highest source of authority for the church. The early churches of the Reformation believed in a critical, yet serious, reading of scripture and holding the Bible as a source of authority higher than that of church tradition. The many cases of abuse that had occurred in the Western Church before the Protestant Reformation led the Reformers to reject much of its tradition. In the early 20th century, a less critical reading of the Bible developed in the United States—leading to a “fundamentalist” reading of Scripture. Christian fundamentalists read the Bible as the “inerrant, infallible” Word of God, as do the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran churches, but interpret it in a literalist fashion without using the historical-critical method. Methodists and Anglicans differ from Lutherans and the Reformed on this doctrine as they teach prima Scriptura, which holds that Scripture is the primary source for Christian doctrine, but that “tradition, experience, and reason” can nurture the Christian religion as long as they are in harmony with the Bible.

“Biblical Christianity” focused on a deep study of the Bible is characteristic of most Protestants as opposed to “Church Christianity”, focused on performing rituals and good works, represented by Catholic and Orthodox traditions. However, Quakers and Pentecostalists emphasize the Holy Spirit and personal closeness to God.

Justification by faith alone:

The belief is that believers are justified, or pardoned for sin, solely on the condition of faith in Christ rather than a combination of faith and good works. For Protestants, good works are a necessary consequence rather than the cause of justification. However, while justification is by faith alone, there is the position that faith is not nude fides.[ John Calvin explained that “it is, therefore, faith alone which justifies, and yet the faith which justifies is not alone: just as it is the heat alone of the sun which warms the earth, and yet in the sun it is not alone.” Lutheran and Reformed Christians differ from Methodists in their understanding of this doctrine.

The universal priesthood of believers:

The universal priesthood of believers implies the right and duty of the Christian laity not only to read the Bible in the vernacular but also to take part in the government and all the public affairs of the Church. It is opposed to the hierarchical system which puts the essence and authority of the Church in an exclusive priesthood, and which makes ordained priests the necessary mediators between God and the people. It is distinguished from the concept of the priesthood of all believers, which did not grant individuals the right to interpret the Bible apart from the Christian community at large because universal priesthood opened the door to such a possibility. Some scholars cite that this doctrine tends to subsume all distinctions in the church under a single spiritual entity. Calvin referred to the universal priesthood as an expression of the relation between the believer and his God, including the freedom of a Christian to come to God through Christ without human mediation. He also maintained that this principle recognizes Christ as prophet, priest, and king and that his priesthood is shared with his people.

Trinity in Protestant Beliefs:

Protestants who adhere to the Nicene Creed believe in three persons (God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit) as one God.

Movements emerging around the time of the Protestant Reformation, but not a part of Protestantism, e.g. Unitarianism also rejects the Trinity. This often serves as a reason for exclusion of the Unitarian Universalism, Oneness Pentecostalism, and other movements from Protestantism by various observers. Unitarianism continues to have a presence mainly in Transylvania, England, and the United States, as well as elsewhere.

Five Solae:

In Protestant Beliefs, The Five Solae are five Latin phrases (or slogans) that emerged during the Protestant Reformation and summarize the reformers’ basic differences in theological beliefs in opposition to the teaching of the Catholic Church of the day. The Latin word sola means “alone”, “only”, or “single”.

The use of the phrases as summaries of teaching emerged overtime during the Reformation, based on the overarching Lutheran and Reformed principle of sola scriptura (by scripture alone). This idea contains the four main doctrines on the Bible: that its teaching is needed for salvation (necessity); that all the doctrine necessary for salvation comes from the Bible alone (sufficiency); that everything taught in the Bible is correct (inerrancy); and that, by the Holy Spirit overcoming sin, believers may read and understand truth from the Bible itself, though understanding is difficult, so the means used to guide individual believers to the true teaching is often mutual discussion within the church (clarity).

The necessity and inerrancy were well-established ideas, garnering little criticism, though they later came under debate from outside during the Enlightenment. The most contentious idea at the time though was the notion that anyone could simply pick up the Bible and learn enough to gain salvation. Though the reformers were concerned with ecclesiology (the doctrine of how the church as a body works), they had a different understanding of the process in which truths in scripture were applied to the life of believers, compared to the Catholics’ idea that certain people within the church, or ideas that were old enough, had a special status in giving an understanding of the text.

The second main principle, sola fide (by faith alone), states that faith in Christ is sufficient alone for eternal salvation and justification. Though argued from scripture, and hence logically consequent to sola scriptura, this is the guiding principle of the work of Luther and the later reformers. Because sola scriptura placed the Bible as the only source of teaching, sola fide epitomizes the main thrust of the teaching the reformers wanted to get back to, namely the direct, close, personal connection between Christ and the believer, hence the reformers’ contention that their work was Christocentric.

The other solas, as statements, emerged later, but the thinking they represent was also part of the early Reformation.

• Solus Christus: Christ alone

The Protestants characterize the dogma concerning the Pope as Christ’s representative head of the Church on earth, the concept of works made meritorious by Christ, and the Catholic idea of a treasury of the merits of Christ and his saints, as a denial that Christ is the only mediator between God and man. Catholics, on the other hand, maintained the traditional understanding of Judaism on these questions and appealed to the universal consensus of Christian tradition.

• Sola Gratia: Grace alone

Protestants perceived Catholic salvation to be dependent upon the grace of God and the merits of one’s works. The reformers posited that salvation is a gift of God (i.e., God’s act of free grace), dispensed by the Holy Spirit owing to the redemptive work of Jesus Christ alone. Consequently, they argued that a sinner is not accepted by God on account of the change wrought in the believer by God’s grace and that the believer is accepted without regard for the merit of his works, for no one deserves salvation.

• Soli Deo Gloria: Glory to God alone

All glory is due to God alone since salvation is accomplished solely through his will and action—not only the gift of the all-sufficient atonement of Jesus on the cross but also the gift of faith in that atonement, created in the heart of the believer by the Holy Spirit. The reformers believed that human beings—even saints canonized by the Catholic Church, the popes, and the ecclesiastical hierarchy—are not worthy of the glory.

Protestant Beliefs | Christ’s presence in the Eucharist:

The Protestant movement began to diverge into several distinct branches in the mid-to-late 16th century. One of the central points of divergence was controversy over the Eucharist. Early Protestants rejected the Catholic dogma of transubstantiation, which teaches that the bread and wine used in the sacrificial rite of the Mass lose their natural substance by being transformed into the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ. They disagreed with one another concerning the presence of Christ and his body and blood in Holy Communion.

• Lutherans hold that within the Lord’s Supper the consecrated elements of bread and wine are the true body and blood of Christ “in, with, and under the form” of bread and wine for all those who eat and drink it, a doctrine that the Formula of Concord calls the Sacramental union. God earnestly offers to all who receive the sacrament, forgiveness of sins, and eternal salvation.

• The Reformed churches emphasize the real spiritual presence, or sacramental presence, of Christ, saying that the sacrament is a sanctifying grace through which the elect believer does not actually partake of Christ, but merely with the bread and wine rather than in the elements. Calvinists deny the Lutheran assertion that all communicants, both believers, and unbelievers, orally receive Christ’s body and blood in the elements of the sacrament but instead affirm that Christ is united to the believer through faith—toward which the supper is an outward and visible aid. This is often referred to as dynamic presence.

• Anglicans and Methodists refuse to define the Presence, preferring to leave it a mystery. The Prayer Books describe the bread and wine as outward and visible signs of an inward and spiritual grace which is the Body and Blood of Christ. However, the words of their liturgies suggest that one can hold to a belief in the Real Presence and Spiritual and Sacramental Present at the same time. For example, “… and you have fed us with the spiritual food in the Sacrament of his Body and Blood;” “…the spiritual food of the most precious Body and Blood of your Son our Saviour Jesus Christ, and for assuring us in these holy mysteries…” American Book of Common Prayer, 1977, pp. 365–366.

• Anabaptists hold a popular simplification of the Zwinglian view, without concern for theological intricacies as hinted at above, may see the Lord’s Supper merely as a symbol of the shared faith of the participants, a commemoration of the facts of the crucifixion, and a reminder of their standing together as the body of Christ (a view referred to as memorial).

World Religions

Read also:

Protestant Religion | Origins & Protestantism around the world

Catholic And Protestant | What’s The main differences between them?

Paganism Religion | Common questions on Paganism Part 2

Church of Scientology & Celebrity Scientologists and Stars list!

Gnosticism today | Is Gnosticism Still Alive?

Simonians | Founder, Beliefs, Doctrine and More